Pegasus, Predator, Hermit Spyware – NSO and its clones

Rise in known exploits point to the proliferation of sophisticated cyber-surveillance tools targeting iOS and Android devices.

The recent revelation that Apple advised iPhone users in 98 countries that they may have been targeted by mercenary spyware is proof of the continuing threat posed by commercial surveillance software. Long gone are the days when the NSO Group’s notorious Pegasus software was the only kid on the block. The growth in the spyware industry is underscored by Google’s February 2024 report “Buying Spying – Insights into Commercial Surveillance Vendors.” The report noted that the emergence of these vendors has created “a lucrative industry used to sell governments and nefarious actors the ability to exploit vulnerabilities in consumer devices….enabling the proliferation of dangerous hacking tools.”

The growth and spread of the industry are reflected in the fact that Google now tracks “40 commercial spyware vendors of varying levels of sophistication and public exposure.” A database of spyware-related incidents cataloged 19 disclosed cases in 2022 alone, involving not just NSO but also fellow Israeli organizations Cytrox, Quadream and Paragon, as well as the Italian company RCS Labs. The difficulty of tackling the use of these sophisticated and invasive cyber-surveillance tools is highlighted by their continued spread, notwithstanding significant actions by the US administration, including the blacklisting of NSO in November 2021, export restrictions imposed on Cytrox and Intellexa, and a visa ban on individuals involved in the misuse of commercial spyware.

A spate of spyware incidents

Since late 2021, we have seen multiple stories about the activities of the surveillance-for-hire industry. The flurry of news started when researchers at the University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab released information about its investigation of Predator spyware produced by North Macedonia-based Cytrox. Citizen Lab identified likely Predator customers in Armenia, Egypt, Greece, Indonesia, Madagascar, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and Serbia. This announcement coincided with Meta’s disclosure that it had banned seven surveillance-for-hire organizations from its platforms, among them the aforementioned Cytrox, together with four Israeli, one Chinese, and one Indian hacking outfit.

In June, we learned about Hermit spyware developed by Italian outfit RCS Labs. Predator has been implicated in an ongoing and politically explosive hacking controversy in Greece, described by Politico as “a scandal that has spiraled into Greece’s own version of the US’s 1972 Watergate intrigue.” It turns out that as the spotlight has been shone on this murky world, we’re discovering that NSO, the now notorious developer of Pegasus, the original iPhone hacking spyware, has many clones and competitors and is “only one piece of a much broader global cyber mercenary industry.”

Surveillance technology has been around for a long time. The security services in Elizabethan England were adept at opening sealed correspondence without detection. More recently, Edward Snowden revealed how the NSA was collecting vast amounts of sensitive data by tapping into the world’s communications networks. The rise in the use of end-to-end encrypted messaging apps such as Whatsapp, Signal, and Telegram meant that network surveillance was ineffective. Spooks wanted access to phones to read the unencrypted version of these messages, and vendors such as NSO emerged to address this need.

Vulnerabilities and Exploits

For those of us working in mobile endpoint security, the most interesting aspect of these reports is the hard evidence they provide of numerous successful exploits of vulnerabilities in mobile phone software. Unlike off-the-shelf malware, which works by tricking end-users into giving dangerous permissions (for example, allowing the app to overlay screens or intercept messages), advanced malware is impossible for end-users to detect and easily evades anti-virus software. It’s exactly this type of threat that mobile endpoint security solutions are designed to address, and the more we know about their operations, the better we can do our job.

Broadly speaking, software vulnerabilities fall into two categories: zero-day and n-day. Zero-day vulnerabilities are unknown to the software vendor. They are the most dangerous because even well-patched devices are unprotected. N-day vulnerabilities are those which are known to vendors. Generally, these will have been addressed in the latest software release, though sometimes the security implications of a bug may be missed, leading to a delay in patching. N-day vulnerabilities matter because we know that only a minority of phones are fully up-to-date at any point in time. Cytrox, the maker of Predator spyware for Android, used a combination of zero-day and n-day vulnerabilities in both Android and Chrome to deploy its malicious software.

In June 2022, Google reported the discovery of Hermit spyware for Android and iOS developed by Italian company RCS Labs. Google identified victims in Italy and Kazakhstan. Researchers believe that the spyware was used to target anti-government protesters in the latter country. The iOS version exploited four n-day vulnerabilities and two zero-day vulnerabilities. All vulnerabilities have now been patched by Apple. Google was unable to provide a comprehensive analysis of the Android version of the spyware, which masquerades as a legitimate Samsung app. The initial download does not contain exploits but instead uses the ‘lower tech’ method of tricking users into granting permissions, which it then abuses. The app has the ability to fetch and run remote modules, which researchers speculate may contain exploits.

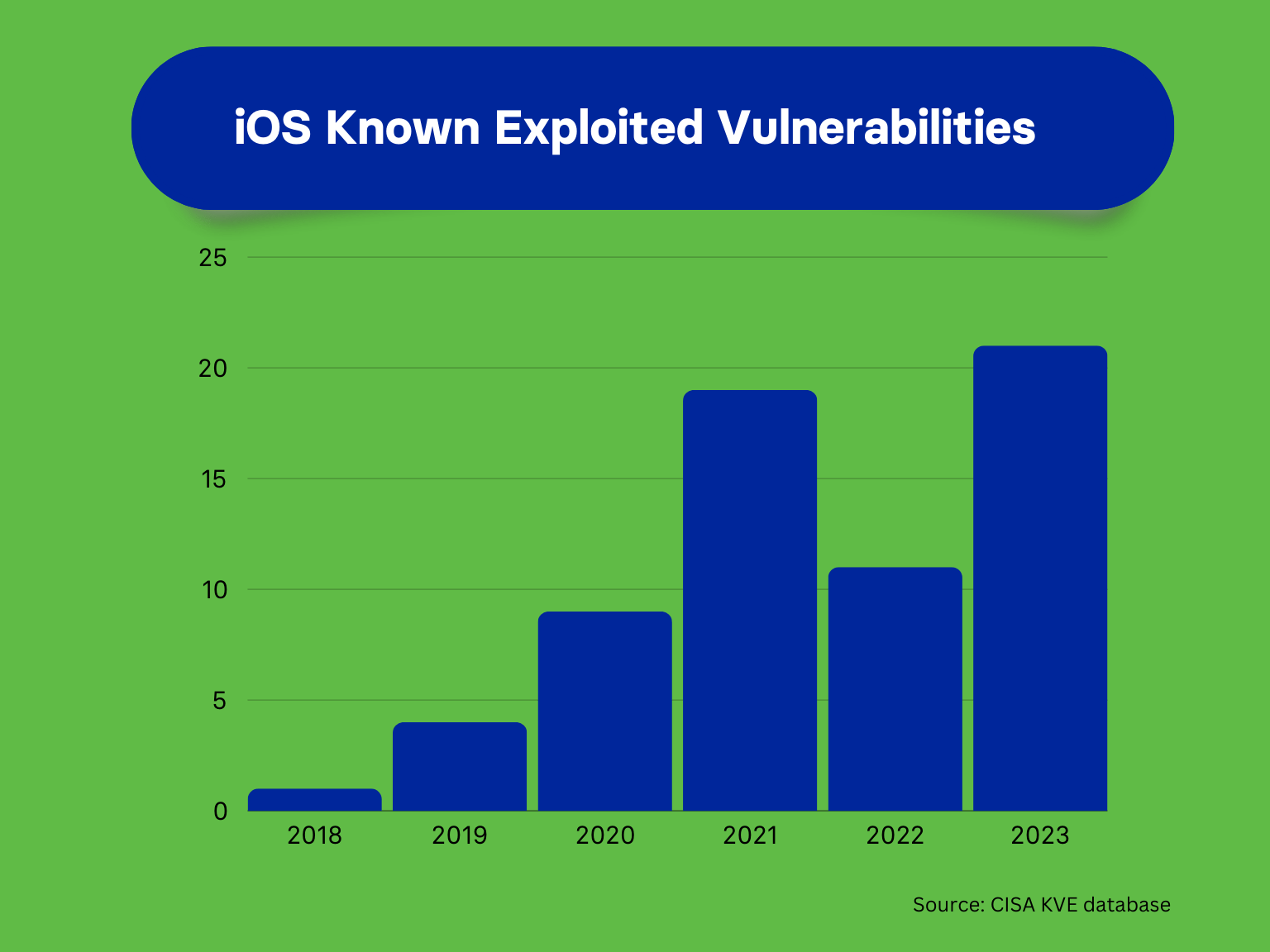

Trend in Known Exploited Vulnerabilities for iOS

Since the beginning of 2023, Apple has released twelve updates to iOS, which included patches for vulnerabilities known to have been exploited. Apple introduced “Rapid Security Responses” (RSRs) in May 2023. So far, two such releases have been published. RSRs deliver important security improvements between software updates.

Over the course of 2023, Apple disclosed a total of 21 known exploited vulnerabilities (KEVs) for iOS. CISA maintains a database of KEVs—vulnerabilities for which there is credible evidence of a successful exploit “in-the-wild.” This was a significant increase on prior years. Does this mean that the iOS platform is becoming less secure? Not necessarily. KEVs are identified in a number of ways. When a researcher flags a vulnerability, Apple’s own telemetry may identify evidence of an active exploit. Alternatively, a forensic investigation of a suspect device may confirm both the presence of a vulnerability and an exploit. Of 2023’s 21 KEVs, 18 were attributed to a range of security researchers, including Kaspersky, Citizen Lab, Google, and Amnesty International. Google’s “Buying Spyware” report noted that half of the zero-day exploits used against its products can be attributed to commercial spyware vendors. It also attributed 9 iOS KEVs to a range of spyware vendors, including NSO Group, PARS Defense, Intellexa, and Variston. So, the constant stream of exploits is most likely due to the growth in the spyware industry.

What’s lurking in the shadows?

The work of digital privacy organizations, NGOs, security researchers, and public oversight bodies gives us important glimpses into the capabilities of mobile spyware, but we must acknowledge how much remains hidden. Most of what is publicly known relates to its use by governments to spy on political opponents. We know much less about spyware developed in-house by security agencies and almost nothing about its use by cybercriminals and hostile nation-states. However, what we have learned is worrying. We now know that multiple commercial spyware vendors have developed tools similar to Pegasus. From Google’s Threat Advisory Group, we learned that they are tracking over 40 vendors selling commercial surveillance products. It would be foolhardy to assume that such tools are not also in the hands of nation-states and cybercriminals. Moreover, recent disclosures have confirmed that the surveillance-for-hire industry has moved beyond targeting politicians and dissidents and is being used for industrial espionage. Black Cube, one of the entities blocked by Meta, has customers across the medical, mining, minerals, and energy sectors and targets organizations in the telecoms, high-tech, legal, financial, and real estate industries.

These revelations have confirmed the existence of multiple tools that have successfully exploited vulnerabilities in both iOS and Android to enable remote access to the full range of smartphone capabilities, including audio, messaging applications, and cameras. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has returned the world to a geopolitics reminiscent of the Cold War. Cyber weapons are increasingly being deployed against civilian targets to disrupt the smooth functioning of the economy and society, as well as for financial gain. Your attackers have both the motivation and the capability to target your employees’ mobile devices. The threat posed to organizations by sophisticated spyware has never been more acute. Let vigilance be your watchword.